European governments have struggled to explain the sudden changes in policymaking during the Trump administration. A common strategy has been to frame the shifts as a part of a more fundamental transformation in global politics, rather than as a surrender under the pressure from the White House. Such a tactic underestimates the public who still remembers European attitude to defense spending before Trump came to office.

A year ago the question was not whether the US would defend NATO countries in case of foreign (=Russian) invasion. The key concern was whether Ukraine had enough armament and personnel to hold on to the rest of its territories. During the campaign trail, Trump promised to solve the situation during day one in office by calling the Russian president. Trump might have thought that his businessman gifts would indeed deliver a ceasefire. Instead the US has heightened uncertainty, not only for Ukraine but for the whole Europe. At times, Trump has been considerably tougher against his supposed allies in Europe than against Putin. Thus, it hardly comes as a surprise that Kremlin continues the offense and displays little appetite for negotiations.

Recently the president of Finland, Alexander Stubb, drew a fascinating parallel from the present day to the era of post-World War restructuring. To be more clear, he pointed towards the post-First World War period and the Cold War period. The former was seen as the tragedy of international institutions whereas the latter as the success story. His argument was as simple as one can expect from a flesh-and-bone politician: countries must do everything to avoid the former scenario from repeating itself by defending the global institutions at all costs. Obviously his words were aimed towards Finnish people who are too well aware how little help Finland received in the outbreak of the Second World War.

A follower of the British media cannot avoid similar comparisons applied to the UK context. Sometimes the parallel with the Second World War is seen in politics when minorities are subjected to discrimination and authoritarian leaders gain popularity. Sometimes it is seen in institutions when criminals in-office cannot be held accountable for their actions and judiciary system becomes politicized. Sometimes it is seen in economics when market fluctuations threaten everyday life and government debt is spiraling out of control. And sometimes it is seen purely in our everyday culture when performing gains upper hand of reasoning and previous moral values are left to decay. Together these depict a world which remains only one step away from the apocalypse.

Previous warnings have been flashing regularly at least from the Global Financial Crisis to the present day. During the heights of euro crisis in 2011, economist Paul Krugman argued that Greece was at 50/50 odds from falling out of euro and drawing others with it to economic chaos. Yet, euro has not only survived from those times, but instead keeps expanding, as it recently added Bulgaria into the bloc. Demise of euro seems almost a laughable prospect today, since it is competing to become a new reserve currency to replace unreliable American dollar.

It is notable, how successfully the global institutions have adapted from situation to another and “muddled through” the crises. The UN continues to form security meetings and provides a forum for all countries to express their concerns through diplomatic means. Likewise WTO, WHO and IPCC among many others continue to function on a global level, despite their limited reach to countries like the US. Unlike during previously mentioned post-war periods, the world continues to hold significant international institutions which cover all the areas of modern life.

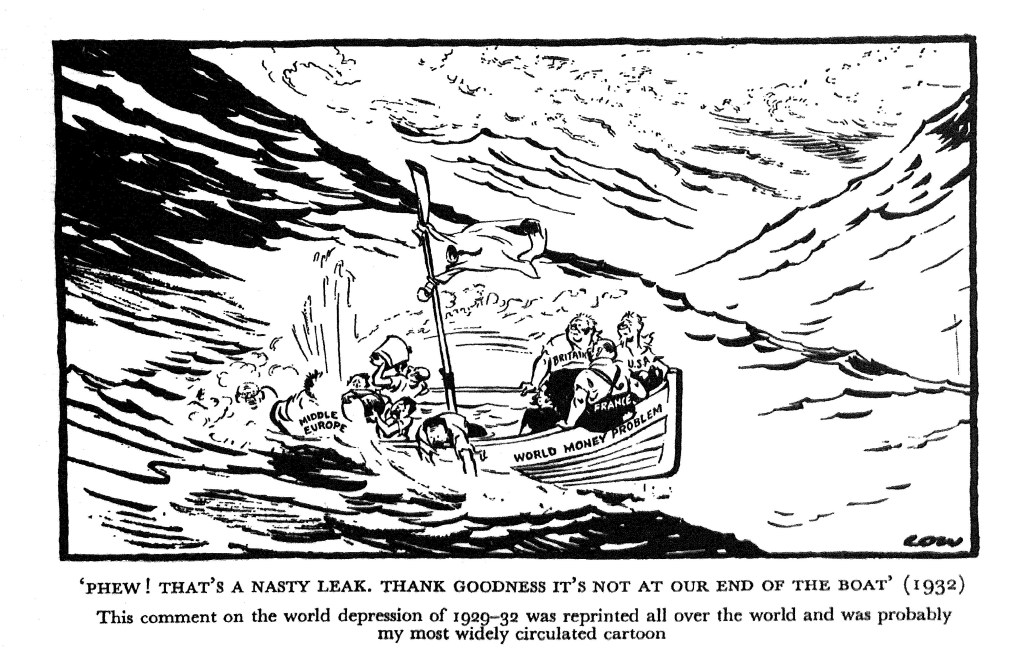

The sheer scale of institutions actually forms a false sense of safety: if the sky has not collapsed already, why should it do so tomorrow or the day after? Such a prognosis is dangerously popular, since it undermines the capability of collective action to prevent crises and allows those in power to take advantages from the many leaks of the old institutional framework. Institutions have their own lifespans and opposition for changes means that they will gradually lose all their credibility.

History does have examples of periods when institutions and norms shifted, when old powers crumbled and new ones emerged. However, I prefer moving further back in time than to the World War periods mentioned in the press all too often. Thus, my next blog post shall delve deep into the midst of the 19th century and cover the parallels between ages of capital and finance, between ages of empire and union . . .

What’s your view?